From the 2018 letter to the shareholders

Our advice? Focus on operating earnings, paying little attention to gains or losses of any variety.

- It is likely that – over time – Berkshire will be a significant repurchaser of its shares, transactions that will take place at prices above book value but below our estimate of intrinsic value. The math of such purchases is simple: Each transaction makes per-share intrinsic value go up, while per-share book value goes down. That combination causes the book-value scorecard to become increasingly out of touch with economic reality.

Focus on the Forest – Forget the Trees

- When we say “earned,” moreover, we are describing what remains after all income taxes, interest payments, managerial compensation (whether cash or stock-based), restructuring expenses, depreciation, amortization and home-office overhead.

- That brand of earnings is a far cry from that frequently touted by Wall Street bankers and corporate CEOs. Too often, their presentations feature “adjusted EBITDA,” a measure that redefines “earnings” to exclude a variety of all-too-real costs.

- Managements sometimes assert that their company’s stock-based compensation shouldn’t be counted as an expense. (What else could it be – a gift from shareholders?) And restructuring expenses? Well, maybe last year’s exact rearrangement won’t recur. But restructurings of one sort or another are common in business – Berkshire has gone down that road dozens of times, and our shareholders have always borne the costs of doing so.

- Abraham Lincoln once posed the question: “If you call a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs does it have?” and then answered his own query: “Four, because calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it one.” Abe would have felt lonely on Wall Street.

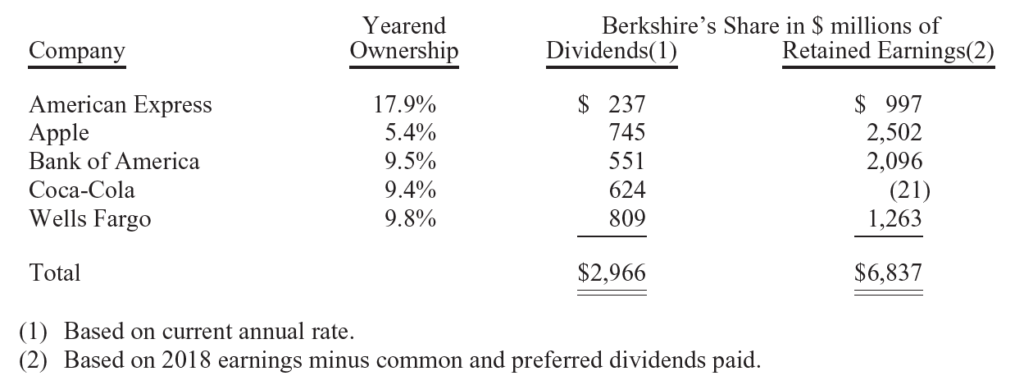

- Our investees paid us dividends of $3.8 billion last year, a sum that will increase in 2019. Far more important than the dividends, though, are the huge earnings that are annually retained by these companies. Consider, as an indicator, these figures that cover only our five largest holdings.

- GAAP – which dictates the earnings we report – does not allow us to include the retained earnings of investees in our financial accounts. But those earnings are of enormous value to us: Over the years, earnings retained by our investees (viewed as a group) have eventually delivered capital gains to Berkshire that totaled more than one dollar for each dollar these companies reinvested for us.

- All of our major holdings enjoy excellent economics, and most use a portion of their retained earnings to repurchase their shares. We very much like that: If Charlie and I think an investee’s stock is underpriced, we rejoice when management employs some of its earnings to increase Berkshire’s ownership percentage.

- Here’s one example drawn from the table above: Berkshire’s holdings of American Express have remained unchanged over the past eight years. Meanwhile, our ownership increased from 12.6% to 17.9% because of repurchases made by the company. Last year, Berkshire’s portion of the $6.9 billion earned by American Express was $1.2 billion, about 96% of the $1.3 billion we paid for our stake in the company. When earnings increase and shares outstanding decrease, owners – over time – usually do well.

But I will never risk getting caught short of cash.

- Our thinking, rather, is focused on calculating whether a portion of an attractive business is worth more than its market price.

- Charlie and I learn of Berkshire’s overall earnings and financial position only on a quarterly basis.

- Over the years, Charlie and I have seen all sorts of bad corporate behavior, both accounting and operational, induced by the desire of management to meet Wall Street expectations. What starts as an “innocent” fudge in order to not disappoint “the Street” – say, trade-loading at quarter-end, turning a blind eye to rising insurance losses, or drawing down a “cookie-jar” reserve – can become the first step toward full-fledged fraud. Playing with the numbers “just this once” may well be the CEO’s intent; it’s seldom the end result. And if it’s okay for the boss to cheat a little, it’s easy for subordinates to rationalize similar behavior.

- This collect-now, pay-later model leaves P/C companies holding large sums – money we call “float” – that will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, insurers get to invest this float for their own benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go, the amount of float an insurer holds usually remains fairly stable in relation to premium volume.

- At rare and unpredictable intervals, however, credit vanishes and debt becomes financially fatal. A Russian roulette equation – usually win, occasionally die – may make financial sense for someone who gets a piece of a company’s upside but does not share in its downside. But that strategy would be madness for Berkshire.

Rational people don’t risk what they have and need for what they don’t have and don’t need.

- As I indicated earlier, about $14.7 billion of our $50.5 billion of deferred taxes arises from the unrealized gains in our equity holdings. These liabilities are accrued in our financial statements at the current 21% corporate tax rate but will be paid at the rates prevailing when our investments are sold. Between now and then, we in effect have an interest-free “loan” that allows us to have more money working for us in equities than would otherwise be the case.

- These companies, also, earn their profits without employing excessive levels of debt (the 15 common stock investments that at yearend had the largest market value).

- On occasion, a ridiculously-high purchase price for a given stock will cause a splendid business to become a poor investment – if not permanently, at least for a painfully long period. Over time, however, investment performance converges with business performance. And, as I will next spell out, the record of American business has been extraordinary.

- The American Tailwind: Let’s put numbers to that claim: If my $114.75 (from 1942) had been invested in a no-fee S&P 500 index fund, and all dividends had been reinvested, my stake would have grown to be worth (pre-taxes) $606,811 on January 31, 2019 (the latest data available before the printing of this letter). That is a gain of 5,288 for 1. Meanwhile, a $1 million investment by a tax-free institution of that time – say, a pension fund or college endowment – would have grown to about $5.3 billion.

- Let me add one additional calculation that I believe will shock you: If that hypothetical institution had paid only 1% of assets annually to various “helpers” such as investment managers and consultants, its gain would have been cut in half, to $2.65 billion. That’s what happens over 77 years when the 11.8% annual return actually achieved by the S&P 500 is recalculated at a 10.8% rate.

- Those who regularly preach doom because of government budget deficits (as I regularly did myself for many years) might note that our country’s national debt has increased roughly 400-fold during the last of my 77-year periods. That’s 40,000%! Suppose you had foreseen this increase and panicked at the prospect of runaway deficits and a worthless currency. To “protect” yourself, you might have eschewed stocks and opted instead to buy 31/4 ounces of gold with your $114.75. And what would that supposed protection have delivered? You would now have an asset worth about $4,200, less than 1% of what would have been realized from a simple unmanaged investment in American business. The magical metal was no match for the American mettle.

Source: http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2018ltr.pdf

Schreibe einen Kommentar